Why Climate Scientists Are Sounding the Alarm on the Ocean Circulation System AMOC

The Equation Read More

Last month, 44 climate scientists from 15 countries wrote an open letter to the Nordic Council of Ministers highlighting the risk of a potential collapse of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC), a critical ocean current system in the Atlantic Ocean. In the letter, the climate scientists stress that the risk of an AMOC collapse due to climate change has been greatly underestimated according to new observational evidence.

Not only would the collapse of the AMOC lead to “catastrophic” impacts on the Nordic countries (Norway, Sweden, Denmark, Iceland, and Finland), but it would also shift weather patterns worldwide. For the United States, an AMOC collapse would lead to warmer ocean temperatures and greater sea-level rise along the East Coast, leading to devastating impacts on fisheries and ecosystems in the coastal Atlantic Ocean, as well as greater flood risk to coastal communities and infrastructure.

The potential collapse of the AMOC—which could happen within this century, or be triggered within this century and play out over a longer timeframe—comes as a result of climate change caused by additional heat-trapping emissions like carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. But what exactly would cause the AMOC to collapse? And if it does, could climate mitigation efforts restart the AMOC to its original circulating strength?

To understand what exactly the AMOC is, a better question to start might be: why does the Earth’s climate system exist? Because the Earth is a sphere, it receives incoming light (electromagnetic radiation) from the sun at different intensities depending on what latitude you’re located at. For example, the polar regions of the planet receive indirect light from the sun, as the sun’s rays are spread out over a larger surface area. Closer to the Equator, the sun’s rays are more direct. This unevenness in sunlight leads to regions closer to the Equator to be warm and regions closer to the North and South Poles to be cold.

The Earth’s climate system does not like imbalances in heat! And that’s why the AMOC exists: it does everything in its power to mix the warm and cold regions together in order to establish an equilibrium. Both the ocean and atmosphere play a role in this mixing—the AMOC is the oceanic piece of this circulation that brings warm ocean water up from the equator to the northern Atlantic Ocean, and then transports colder water back to the equator in an attempt to even out the differences in temperature (Figure 1).

In addition to transporting warmer water north and cooler water south, the AMOC also mixes an imbalance in salt levels in ocean water. Water near the Equator is much less salty than water in the North Atlantic. Why? The Tropical Atlantic Ocean receives significantly more rainfall than the North Atlantic, where it rains much less. More rainfall in the Tropical Atlantic Ocean results in less salty water. This imbalance in the climate system forces the AMOC to transport fresh, warm (low density) water north and salty, cold (high density) water south.

The AMOC is a vital circulation of our climate system, and because of all the warm water it transports to the North Atlantic, human civilization has flourished in very high latitudes in Europe, as well as allowing the development of complex ocean dwelling life and ecosystems.

Picture Quebec City in Canada and London in the UK. Quebec City is famous for its winters with snow and sub-zero temperatures. London, on the other hand, barely receives snow, even during the winter season. But here’s the kicker—London is significantly further north (closer to the North Pole) than Quebec City. London is warmer despite it being further north in part due to the existence of the AMOC, which brings warm water up from the Equator to northern Europe.

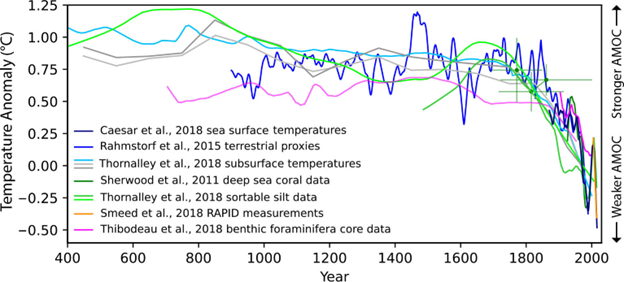

As global temperatures warm due to human-caused climate change, the Greenland ice sheet is melting rapidly, leading to vast amounts of freshwater entering the North Atlantic. Because of this, the ocean waters in the north are less salty and less dense than before. This partly reduces the density imbalance between the Equator and the northern Atlantic Ocean, resulting in the AMOC to weaken or potentially collapse (Figure 2).

The idea of a potential AMOC collapse is not new: some scientists were already thinking about this in the early 1960s. However, with the advent of sophisticated climate models in recent decades, climate scientists are better able to study what exactly happens when freshwater increases in the north Atlantic Ocean, forcing the weakening of the AMOC.

In the early phases of a weakened or collapsed AMOC, huge changes would be expected in the local climate of northern Europe. Scandinavia, the UK, Iceland, and Ireland would experience winters much colder than currently observed, with weather becoming even more unpredictable. In fact, in the open letter published last week, there is a dire warning that a weakening AMOC “would potentially threaten the viability of agriculture in northwestern Europe.”

But the impacts of a weakened or collapsed AMOC would spread worldwide. As the AMOC circulation weakens, warm water would start to pool up against the eastern North American coast, leading to significantly warmer ocean temperatures and higher sea level rise compared to other regions across the globe. Near the tropics, monsoon patterns and other tropical rainfall belts would shift. Globally, the circulation of the atmosphere, which governs where weather patterns set up, would change in intensity. All of this as a result of an oceanic circulation in the Atlantic Ocean slowing down.

Why did this group of scientists suddenly sound the alarm? In the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Sixth Assessment Report, published in 2023, scientific consensus stated that there was a “medium chance” the AMOC would collapse before the end of the 21st century. However, four recent peer-reviewed observational studies have found that the AMOC is in fact already showing signs of collapse (see references 6-9 in the open letter).

In one study published in Science Advances, scientists developed a physics-based early warning signal for an indication of when AMOC could be heading towards a collapse. Unfortunately, they found that based on observations, the AMOC has already weakened so much that the Earth is closing in on a tipping point with the AMOC potentially collapsing.

If the AMOC did collapse, it would be nearly impossible to bring it back to life. In physics-based and climate modeling simulations, the AMOC experiences something called hysteresis. Hysteresis is a phenomenon where any change to a system, such as the AMOC, depends on its history. The AMOC has existed and persisted for thousands of years in the stable pre-industrial climate. Therefore, it’s difficult to force the AMOC out of its current circulation state. If we reach the tipping point of an AMOC collapse, it would be very difficult to change back to a circulating state, simply because the AMOC would need a lot of push to get it going again.

Dozens of climate scientists have sounded the alarm for the Nordic Council of Ministers. They do not discuss the potential of the AMOC collapse lightly, as it would directly affect and have devastating impacts on the communities that many of these scientists live in.

Perhaps even more alarming is the language around their call to action: they recognize that adaptation for citizens in the Nordic countries to an AMOC collapse is not a “viable option,” and that the leaders of these countries should instead “take steps to minimize this risk as much as possible.”

The scientists call on the leaders of these countries to use their international standing to push world governments to take drastic steps to cut the release of heat-trapping emissions and stay close to the 1.5-degree Celsius target set by the Paris Agreement. However, current estimates from the United Nations Emissions Gap Report predict we’re on track to warm 2.6-3.1 degrees Celsius.

Will the world’s governments and corporations heed the warning from these scientists? We hope so. Countries must do everything in their power to drastically reduce heat-trapping emissions, and we must hold governments accountable to protect the oceanic circulation in the Atlantic Ocean, and limit the risk of its collapse and the potential to upend civilization in northern Europe and beyond.