Soaring Insurance Rates Show Climate Change Is a Pocketbook Issue

The Equation Read More

As 2024 winds down, with its parade of climate-and extreme weather-fueled disasters, people across the nation are feeling the sharp pinch of rising insurance premiums and dropped policies. There are other factors at play here—including growing development in flood-prone and wildfire-prone areas and fundamental inequities and information gaps in the insurance market—but all of that is being exacerbated by worsening flooding, wildfires and intensified storms. Policymakers and regulators must act quickly because the market is not going to solve this problem on its own, and it’s definitely not going to do it in a way that protects low- and middle-income people.

Please see earlier blogposts I’ve written on this topic to learn more.

Despite the many headlines and heart-breaking stories about the impact of high insurance costs and dropped policies, there’s a lack of publicly available, granular data on where and how much premiums are increasing and why.

Earlier this year, the US Department of the Treasury’s Federal Insurance Office (FIO) and the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) announced a first-ever data call to assess how climate risks were affecting the insurance market. This is a voluntary effort and some states, including Florida, Texas and Louisiana, have already signaled they will not participate. That’s a problem because these are also states where consumers have experienced sky-rocketing rate increases and insurers dropping policies or even exiting the market entirely—and they are highly exposed to climate risks.

According to an annual report from the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), “The data call required participating insurers to submit ZIP Code-level data on premiums, policies, claims, losses, limits, deductibles, non-renewals, and coverage types for the ZIP Codes in which they operate nationwide. State insurance regulators sought more than 70 data points. An anonymized subset of the data was shared with FIO.”

Yet, none of that data has been shared publicly. That’s why UCS has joined in signing a letter from a group of organizations, calling on FIO to release the data so it’s available for local planners, policymakers, decisionmakers, scientists and community-based organizations to have a better understanding of how best to address this rapidly growing problem.

Private insurers are holding a lot of proprietary data that regulators and the general public do not have access to. This creates a gap in information—an information asymmetry—that can prevent people from making informed decisions and prevent the market from functioning well. A lack of freely available, localized information about climate risks and projections is also part of the challenge for many communities and homeowners.

The insurance crisis is now a nationwide problem, spilling into parts of the country that may not yet be on the frontlines of climate risks, and into the broader insurance market beyond property insurance. Congress must step up to examine the problem and propose solutions, working alongside state regulators.

That’s why it’s heartening to see that Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) and the Senate budget committee are holding a hearing on December 18 on the climate-driven insurance crisis. Among the witnesses is Dr. Benjamin Keys, who has done important work in highlighting the role of climate risks in driving increases in insurance premiums.

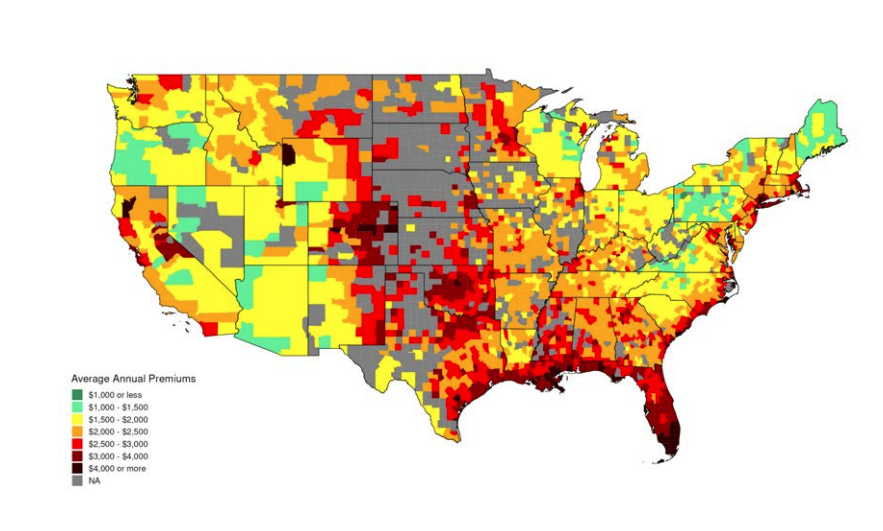

According to his research, homeowners in the US saw their annual insurance premiums increase by an average of 33% or $500 between 2020 and 2023. Further, his work analyzing premium increases at the county level shows a stark correlation with places that are more exposed to climate risks.

Average annual insurance premiums in the first half of 2023 by county

Source: Keys and Mulder, 2024 https://www.nber.org/system/files/working_papers/w32579/w32579.pdf

Earlier this week, Democrats on the Joint Economic Committee, chaired by Senator Martin Heinrich (D-NM), released a report highlighting the growing risks of climate change to insurance and housing markets.

The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office has also released a recent report and conducted recent briefings on climate change, disaster risk and homeowner’s insurance. One of the challenges they point out is that, even as disasters are worsening, many people are underinsured.

Low- and moderate-income households are more likely to be underinsured. According to their report: “In 2023, insurers covered $80 billion of the $114 billion of losses attributable to natural disasters, meaning that 30 percent of those losses were not insured.” With insurance premiums increasingly unaffordable, that gap in insurance will likely increase as many people may be forced to go without.

There are important ways insurance affordability could be tackled by policymakers, including increasing access to parametric insurance, microinsurance programs, and community-based insurance, as well as passing legislation to include means-tested subsidies in the National Flood Insurance Program. Parametric insurance contracts can help simplify and speed up payouts since they are set up based on specific disaster thresholds being crossed (e.g. an earthquake of a certain magnitude or a hurricane with a specific wind speed), rather than being based on an actual evaluation of loss which can take time. Microinsurance programs can provide low-income households access to basic insurance with lower premiums and less comprehensive coverage. Community based insurance is purchased at the community level instead of individual households.

Insurance companies should also be required to provide more information about why they are increasing rates, how they determine the magnitude of the increases, and what incentives they provide to help homeowners reduce their premiums by investing in risk reduction measures. Regulators must ensure that insurers are not discriminating against low-income policyholders or dropping less profitable lines under the guise of climate impacts.

The crisis in the insurance market we’re seeing today was entirely foreseeable, and largely preventable if we had acted earlier to limit the heat-trapping emissions driving climate change, invest in climate resilience, and enact equity-focused reforms in insurance markets. Climate scientists have been sounding the alarm for decades, and yet the market and policymakers have reacted with short-term strategies because those are the timeframes for determining shareholder value, profits and elections.

As we look to find ways out of this crisis, let’s keep in mind the continued mismatch in time horizons for decision making in the insurance marketplace and the climate impacts we have unleashed and are locking in for the long term by continuing to burn fossil fuels today. And, in an outrageous contradiction, the insurance industry continues to insure the build-out of fossil fuel infrastructure!

Data from Swiss Re shows that, globally, insured losses will exceed $135 billion in 2024. Two thirds of that happened in the US, with Hurricanes Helene and Milton alone causing $50 billion in insured losses.

US insurance companies will very likely hike rates again in the new year as global reinsurers reset their rates to reflect the growing costs of disasters worldwide. Rate hikes will hit homeowners hard. Renters, too, as landlords are increasingly passing through this increase in insurance costs in the form of higher rents, thus worsening the housing affordability crunch. More people will find their monthly budgets stretched or be forced to go without insurance and live in fear that they won’t be able to recover from the next disaster.

The question for policymakers and regulators is whether they are willing to take bold action to help keep insurance available and affordable wherever possible (which unfortunately won’t be everywhere); help people invest in resilience measures to keep their homes and property safer in a warming world; help provide options for people to move away from the highest risk places; and help cut the heat-trapping emissions driving many types of extreme disasters.

Insurance is one important tool. Let’s make sure it’s working well, guided by the latest science and with strong oversight and equity provisions. And let’s invest in a whole range of necessary actions to complement that because the current insurance crisis is likely just the tip of the iceberg.

Climate risks are not just affecting the insurance market but also the housing and mortgage markets. And it isn’t just insurance that is increasingly hard to buy, finding safe, affordable housing in places protected from climate extremes is a growing challenge for many low- and middle-income people.

One thing we can’t afford our policymakers and decisionmakers to do is to deny that climate change is an economic and pocketbook issue.