How Transmission—Not Gas—Will Bolster Winter Grid Reliability: A Look at MISO South

The Equation Read More

As the year kicks off with a very cold January weather forecast, US power grid operators and the regulators who oversee them are paying close attention to ensure that the grid failures of several past extreme winter storms don’t happen again. These dangerous grid failures over roughly the last decade have left millions in the dark and cold, sometimes with tragic and deadly consequences. Clean energy solutions are readily available to help ensure that these failures don’t reoccur, and long-range transmission lines are one of the key components of these solutions.

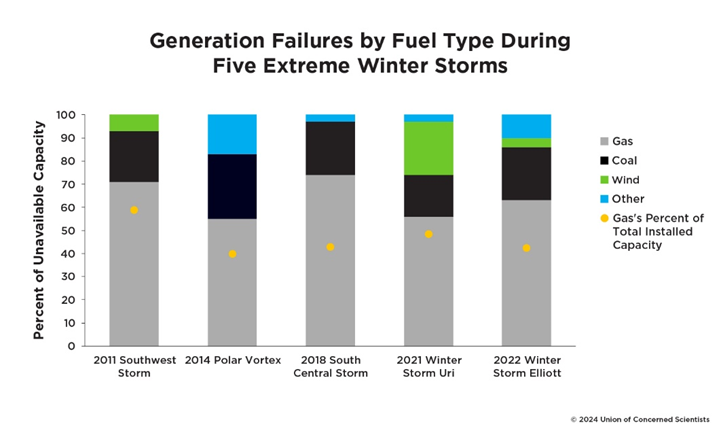

Increasing the country’s long-range transmission capacity will allow much more renewable and energy storage capacity to come onto the grid. This new generating capacity, coupled with more transmission capacity, will enable us to share far more electricity between regions during extreme weather events. It will also allow us to reduce our reliance on centralized thermal power plants, such as gas plants, which have been disproportionately vulnerable to failure and the largest contributor to grid reliability problems during recent winter storms.

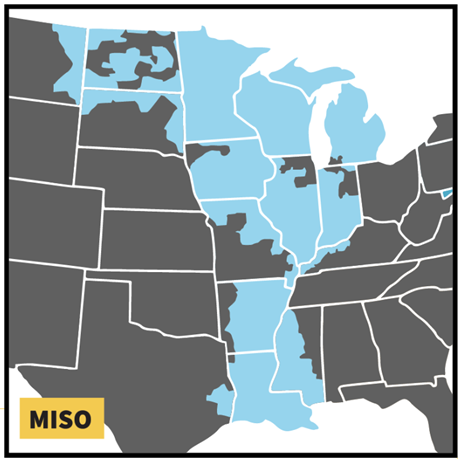

Although many areas of the country need much more transmission capacity, in this blog I’ll focus on one particularly transmission-constrained region often hit by winter storms as an illustrative example of how transmission is key to strengthening winter grid reliability: that’s the Midcontinent Independent System Operator’s (MISO) southern region, or “MISO South.” This region covers most of Louisiana, parts of Mississippi and Arkansas, and a small portion of eastern Texas.

And while the United States as a whole is very over-reliant on polluting gas plants, which make up 43% of the country’s total generating capacity, MISO South is even more so , with gas making up roughly 60% of its total generating capacity. This drastically high over-reliance on extreme-weather-vulnerable gas plants—coupled with persistent influence by utility companies seeking to maintain low transmission connectivity to other regions—has put people in MISO South at serious risk during recent winter storms.

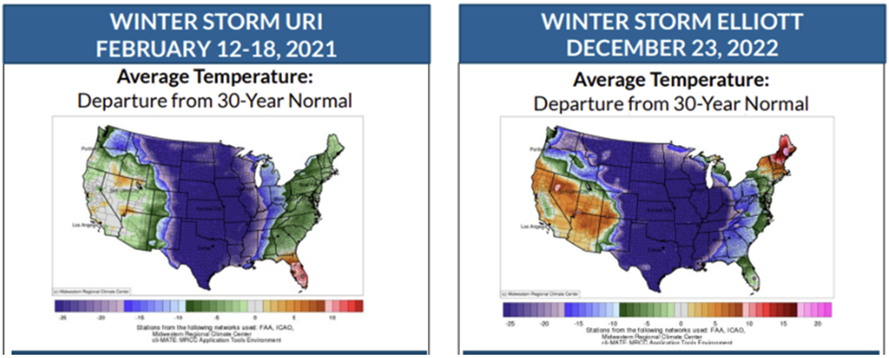

As I wrote last year in a blogpost explaining how gas plants fail in winter storms, the area of the country that has experienced dangerous winter storms in recent years is very, very large.

The MISO South region was often right in the middle of these large footprints of recent cold snaps and extreme winter storms. Communities in this region, just like those served by Texas’s main grid operator (the Electric Reliability Council of Texas, or “ERCOT”), experienced the worst impacts during Winter Storm Uri in 2021, when MISO had to shut off power to customers via rolling blackouts as demand soared and electricity supply continued to be knocked offline by the intense cold weather and freezing precipitation.

(Note: Grid operators implement rolling blackouts, or “firm load shedding”, when electricity demand exceeds available supply. These outages differ from other, more common types of outages.)

An area in eastern Texas experienced the longest rolling blackouts of any other customers within MISO. The grid operator ordered the utility company Entergy Texas to cut power to some of its customers to reduce the load on the transmission system, and the power wasn’t fully restored to all of those customers until more than 30 hours later. Although much shorter than the 4.5 days that some households within ERCOT went without power, 30 hours is still a dangerously long time to go without power in such extreme conditions, as most households in Texas use electricity for heating. Even the minority of homes that use gas furnaces generally need electricity to start and fan heat throughout the home.

As storm Uri persisted, MISO directed utility companies to cut power to an even greater number of customers in Louisiana, and a relatively smaller amount of customers in Illinois in its northern region. Eventually, MISO had to order power cuts to some customers spread out across its entire southern region. Hundreds of thousands of households in the region ultimately lost power amid dangerously cold temperatures.

These risks to Entergy customers and others in Louisiana, Texas, Mississippi and Arkansas are well known. Utilities and regulators in these states have resisted the transmission planning that MISO proposes to address this problem. Investor-owned utilities want to protect the bottom line of their fossil fuel power plants and stave off competition from low-cost renewables that would be aided by transmission, even if those cleaner solutions would help ratepayers and boost grid reliability.

For MISO, there were warning signs leading up to Winter Storm Uri, the most prominent being a January 2018 winter storm that prompted a second-tier grid emergency in MISO South, just one tier below rolling blackouts. And less than two years after the failures of Uri, Winter Storm Elliott hit in December 2022, prompting MISO to declare yet another second-tier grid emergency. This level of emergency is declared when grid operators no longer have the required level of “reserves”—essentially, extra generating capacity to serve as a buffer.

These three recent winter storms that significantly impacted MISO South had two key features in common: 1) widespread gas plant outages and 2) transmission congestion that threatened grid reliability. (Similar to how roads get congested with cars, transmission lines often get “congested” because they can only safely carry so much power. More on this in the next section.)

Regarding the first feature, widespread gas plant failures are a huge problem during extreme weather events such as winter storms, but I won’t go into detail in this blogpost. I encourage readers to check out the UCS issue brief from last year that was referenced in the introduction if they want to learn more.

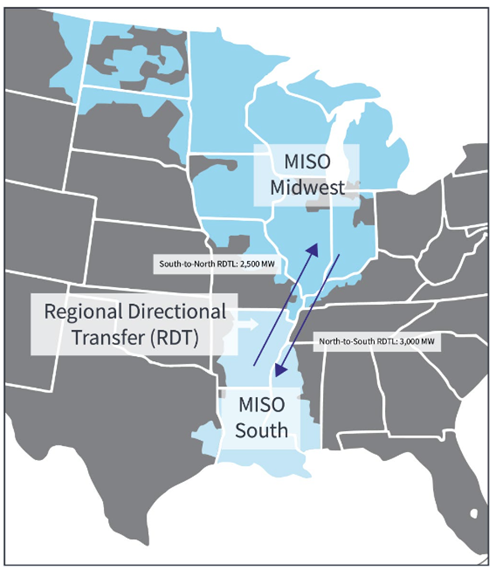

In terms of transmission connectivity, the MISO South region is a bit of an island within the larger US power grid. While it’s certainly more connected to other regions compared to Texas’s main grid, ERCOT (ERCOT’s isolation was one of the primary reasons Winter Storm Uri was so devastating to Texas), MISO South has relatively few connections to neighboring regions in the southeast, ERCOT, the Great Plains region, and its own northern counterpart covering a large chunk of the Midwest (“MISO Midwest” or “MISO North”). This lack of interregional (as well as intraregional) connectivity often leads to high transmission congestion, which can cause serious problems during extreme winter storms when demand is very high.

Currently, MISO only has enough transmission capacity to send about 3,000 MW of power from its northern region to its southern region, less than 10% of MISO South’s peak load. Instead of using infrastructure within its own footprint, MISO largely relies on neighboring grids’ transmission infrastructure to send that power between its northern and southern regions under a contract with the Great Plains grid operator Southwest Power Pool (SPP) and six other neighboring grid operators.

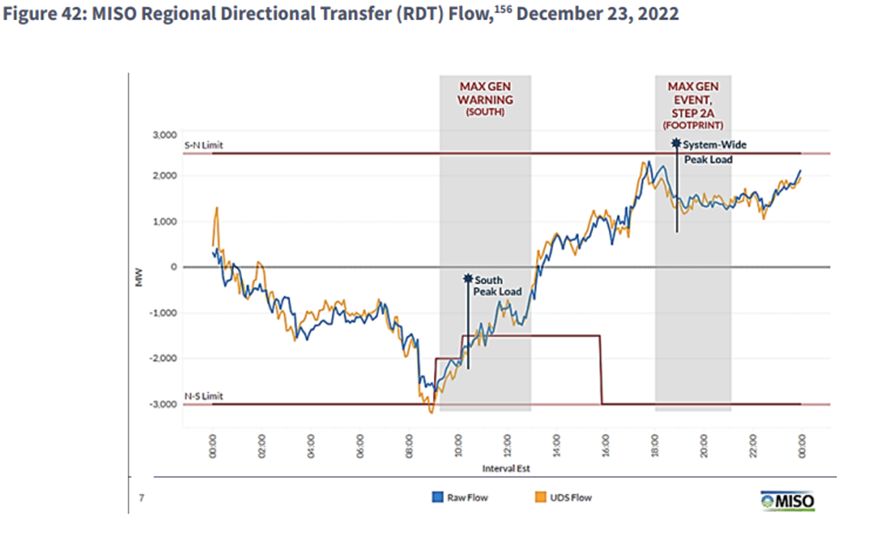

During the early stages of Winter Storm Elliott, as demand rose above forecasts, power plants in MISO South started getting knocked offline. MISO then directed north-south power transfers to keep the grid reliable, nearly reaching the 3,000 MW limit specified in its contract with neighboring operators.

But at roughly the same time, one of those neighboring operators, SPP, was also experiencing very high demand amid rising generator outages and some transmission outages. These tightening grid conditions prompted SPP to ask MISO to cut the transfer limit in half to maintain stability on its system. This reduction from a 3,000 MW limit to just 1,500 MW left communities in MISO South even more transmission-isolated and at greater risk of experiencing rolling blackouts again, just as they had less than two years earlier.

When MISO South did experience rolling blackouts less than two years prior during storm Uri, the north-south transfer limit was actually briefly exceeded, which the contract with its neighbors allows for in certain emergencies.

This type of transmission congestion was also a feature of the 2018 winter storm, when MISO was just one large generator outage away from having to implement rolling blackouts in MISO South. The north-south power transfer limit was exceeded, and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) found very plainly after the storm that “MISO had reserves that were stranded in its northern footprint, limited by transmission system constraints.” MISO South, over-reliant on gas and other power plants that were failing, couldn’t access MISO North’s extra power due to low transmission capacity.

Part of this extra capacity in MISO North came from the region’s vast amount of wind power, which reached record levels during the 2018 winter storm. During storm Uri in 2021, solar power outperformed neighboring ERCOT’s expectations, and research shows that had more solar capacity been built, rolling blackouts would have been significantly reduced. And while MISO declared a “maximum generation warning” during storm Elliott in 2022 in its southern region—likely prompting older, dirtier and costlier plants to ramp up—wind resources in MISO North at certain points during the storm generated more than five times the power they had committed to provide.

Our grid will be much more reliable during these dangerous winter storms if we diversify away from fossil fuels and toward renewables, and if we build more transmission capacity to transport the electricity to areas where it’s needed most. Study after study shows that a geographically diverse mix of clean energy solutions, such as renewables and energy storage facilitated by a robust transmission system, can reliably power a net-zero-emission grid (and fossil fueled power’s reliability is often overestimated in these energy modeling studies).

A clean grid also brings the added massive benefits of decreasing public health costs from pollution and mitigating climate change, which is exacerbating the extreme weather events that are currently making our grid less reliable.

Consumers will also save a lot of money directly as more transmission is added by getting access to more wind and solar power, which costs nothing to produce once it comes online. The value of these clean resources is especially pronounced when gas prices skyrocket during winter storms. One analysis calculated during storm Uri, ratepayers would have saved $85 million per 1,000 MW of additional transmission connecting MISO North to MISO South.

Even in normal weather, ratepayers will benefit from more low-cost renewables aided by a strong transmission network. A study published earlier this year found that customers of two large MISO South utilities, Entergy Louisiana and Entergy Arkansas, could have saved more than $900 million in 2022 alone if the region were more connected to MISO North and SPP.

This latter finding starts to make sense when you consider the massive—and increasing—amount of affordable wind power in MISO North and SPP getting thrown away, or “curtailed”, due to transmission constraints. Ratepayers in MISO South could use that more affordable power but cannot currently access it.

There are reasons to be optimistic that these benefits of renewables and transmission—in terms of reliability, public health, consumer costs, and climate—will be realized. FERC recently approved $1.8 billion in transmission investments better connecting SPP and MISO North, which could spur an estimated 29,000 MW of renewables. And just last month, MISO approved nearly $22 billion in transmission projects within MISO North, which will facilitate about 100,000 MW of clean resources and deliver tens of billions of dollars in net benefits.

But despite this transmission planning for the north, communities in MISO South states—Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi and eastern Texas—remain exposed by the decisions and resistance of their utilities and state regulators with power that is dirtier, more expensive, and less reliable, due in large part to transmission congestion and isolation. Federal policymakers must take action to better integrate the country’s various regions of the grid by, for example, finalizing its national interest transmission corridors, which includes a corridor connecting MISO South to SPP and would greatly facilitate transmission development on a reasonable timeline.

In addition, as happened in MISO for its northern region, state officials and utilities must recognize the opportunity to protect public health and safety by supporting another planned tranche of investments (dubbed ‘Tranche 3’) aimed at building out the transmission network within MISO South. This will be followed by another tranche of investments (‘Tranche 4’) that will connect MISO North and MISO South. Every year this development is delayed is another year communities in these southern states are put at greater unnecessary risk of experiencing blackouts, breathing more polluted air, and paying for expensive power when more affordable power is available elsewhere.